Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE) is a road map of sorts that can steer a company’s production processes (including packaging) to greater efficiency and profitability. Yet in most North American plants, OEE averages 40% to 50% (out of a possible 100%), with “pharmaceutical firms lucky to be half that, if measured properly.”

That was the opinion shared by Paul Zepf during his presentation, “How Pharmaceutical Packaging Lines Can Increase Profitability: The Importance of OEE,” at the third Pharmaceutical Packaging Forum (PPF, www.packworld.com/ppf) held in April in Philadelphia. Zepf, M. Eng., P. Eng., CPP at Zarpac, Inc. (www.zarpac.com), has more than 36 years of packaging production experience around the globe.

Zarpac is an Oakville, Ontario, Canada-based international production, engineering, and consulting firm that works on systems integration, line design and installation, and training, with considerable experience in pharmaceutical plants. Zepf, a co-founder of the company, teamed up with Summit, publishers of Packaging World and Healthcare Packaging magazines, to conduct a series of Packaging Line Performance Workshops around the U.S. in 2008.

He says production inconsistencies exist worldwide, and North America is not immune to them. “The concern,” he said, “is that we need to produce the highest-quality products at the lowest price when needed, but when I go into production facilities, I see we habitually produce questionable products of dubious quality at the highest price whenever we can get it done, and that’s unfortunate.”

Food and Drug Administration guidelines require that product manufacturers not only validate their production and packaging processes, but demonstrate control and consistency. Yet Zepf consistently sees inconsistencies in many facilities that not only reduce efficiency and productivity, but are not consistent with current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMPs).

Said Zepf, “You could probably go back 50 years and have said the same thing. The lack of understanding of how we make our profits is truer today than yesterday. Many people have no idea what’s happening in their production systems. The value and timing of information from the line’s performance three months ago, for example, may give you some historical perspective, but it’s no good in the sense that you don’t make money looking at data. You make money by making and selling products, and you need to follow cGMPs.”

Another problem identified by Zepf at the PPF: “The production personnel lack direction, support, discipline, authority, and accountability. And because a lot of us older guys are now retiring, there’s sort of a vacuum where everybody’s learning again by mistakes. So there is very little mentoring left and few skilled people to pass along the information. They lack the tools and skills to affect positive change and operations in a timely manner. There are lots of tools out there and many different ways of looking at production systems, yet most people don’t even know that they even exist, let alone how to use them.”

Determining OEE

Zepf explained that for the OEE “tool” to serve as the roadmap to “tell you how to achieve your goals, there needs to be a top-down cultural change; you need a holistic approach. In practice, if you don’t do that, it causes a lot of problems. That’s why there are a lot of failures in lean manufacturing or Six Sigma approaches.

“Nowadays, when I go into a plant, most people cannot explain their process. OEE sort of forces you into that holistic process,” he said.

Zepf related one instance where a plant employee told him the plant was operating at 148% efficiency. “As an engineer, you have to say well, wait a minute. It’s impossible to get more than 100 percent.”

Just determining OEE is a complex process. Zepf noted, “OEE is known, but is widely misunderstood and often used incorrectly. Most people base OEE on machine availability, but it’s also tied into the cost of quality. That phrase, cost of quality, goes back to the 1920s and was developed during World War II. Of course, after the war, we threw it all out. The United States sent it all to Japan, and now it’s come back to haunt you. So OEE is just an overall picture-window-view of the cost of quality.”

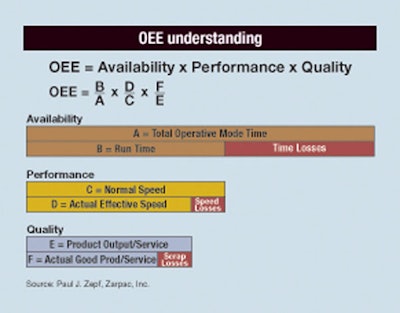

He says, “A Google search for OEE will give you a definition about availability times performance times quality, which is nice, but it doesn’t really help that much in packaging. OEE looks at anything to do with that operation, including sanitization, lunches, breaks, start-ups, and meetings, all of which are part of the operative mode of that system or line. When you do that, it presents a little bit different picture of your performance. It looks at actual speed versus what speed it could run at. You can determine quality output versus scrap and determine the cost of quality. OEE lets you break your process down mathematically.”

Factoring speed, scrap, and ramping rates

Speed and scrap are related in that the number of products produced per minute on each of the machines on the line varies. Scrap losses have to be added in, as well as buffers. Understanding the process will dictate whether buffers are required or not. Buffers, when applied and designed correctly, modulate the output of the line and maximize uptime by keeping machines running by covering the Mean Time To Repair (MTTR) of the critical machine(s). “In my workshops, I’m always recommending that companies first fix up and maximize existing lines before they invest in another line. That way, they can put all the good habits developed on their older lines and apply them to the new line to get what they want designed into that new line.”

He believes it’s good practice to determine the most critical machine on your packaging line. “For most pharmaceuticals, you can say it’s the filler,” said Zepf. “The theory says to ensure that everything upstream gets product to the critical machine so that it is never starved; and therefore, downstream product must always be removed so that the critical filling machine is never blocked.”

Zepf explained that OEE involves determining the line’s ramping rate divided by the normal rate. That’s what OEE in packaging defines as performance. “A lot of people have strange ideas of how they use rates to get this value performance,” he said. The line’s normal speed (or speed determined by design to fulfill customer requirements of volume and quality within specific time constraints) rate may be 240 per minute. An operator may say ‘Well, things aren’t running too well, so I’m going to run at 220 today.’ This unilateral adjustment now causes degradation. But the classic is lunchtime, where the machine or entire system goes down, purges out, and then is restarted. So what’s the average number of times that a production system will go down in any given eight-hour shift?” he asked. “It’s often 80 to 100 times. If you lose seven seconds or 10 seconds for every down and up, that’s a lot of time. That has to be figured in there too, and that’s the ramping rate.”

Line ‘availability’

In looking at machine and line availability time, factor in both planned and unplanned events. He said, “Planned downtime is that time in which management dictates operative processes that yield no output. It goes right down to specifics, such as if you bought a machine that has to change a film roll,” Zepf explained. “If there is no auto-splice, then changing the film roll is planned downtime, as are lunches, breaks, changeovers, meetings, etcetera. Unplanned is anything that you have no control over or are unexpected events.”

In measuring OEE, some companies exclude factors such as lunch and even breaks. “They may say they have an OEE of 80, which is false. You can fool yourself, but the reality of it is you may have a lot of problems you’re masking and will never correct them if they’re not in front of you. With OEE, all of these events are meant to be looked at,” said Zepf. “Is a 30-minute lunch really 30 minutes?”

Availability is best determined by factoring the actual engineering definition of uptime and downtime: Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF) divided by MTBF plus MTTR. There are data acquisition and analytic systems, including those sold by Zarpac, that can automatically track and analyze this type of data on a packaging line. The technology now exists to do these activities quickly, accurately, and economically, he noted.

A “World Class” machine, said Zepf, is one that runs at least 97% of the time, based on a month’s worth of run operation, or at least 20 shifts of back-to-back production. “Very few machines do that,” he noted. “You might be able to get that for a couple of shifts, but doing that during the course of a month is a tall order.” Reaching that level on a line full of machines becomes an even taller order.

Fixing your OEE

“When I go into a lot of plants, the first thing that they tell me is fix the machines,” Zepf told the PPF audience. “The fact is that even if you’re running at 85 percent OEE, there are machine issues. There’s no such thing as a perfect machine. The question is, ‘Where do I start?’ If you’re at less than 50-percent OEE, you don’t start at the machines.”

Zepf said there are several pieces of low-hanging fruit that offer good places to start. “Look at quality issues, particularly scrap,” he advised. “This is sometimes difficult to get at. Scrap really is the subset of waste, which includes any human or machine activity that absorbs time, resources, materials, money, and/or effort, but creates no value, or reduced value. When you talk about the waste, you have to also consider rework, which is very difficult to assess on most production lines. Determine what causes scrap. Maybe it’s in the design of the machine or line, or possibly it’s equipment or inputs that are manufactured out of spec.

“There’s a whole list of things that you can identify as scrap. Trash from when you have a failure in a machine and the machine is shut down is one event where workers are in a hurry to fix the problem and get the line back up and running. So they’re not too selective. They’ll grab a whole bunch of product and dump it all. Studies have indicated that if you examine what they dumped, 50 percent to 70 percent of it is good product, but because they’re in a hurry it becomes scrap. If you do that maybe 40 or 50 times a shift, how much good product did you throw away?”

A simple way to calculate scrap, Zepf contended, is to use automatic data collection tools. In other words, “if you put 20,000 caps into the line but only 15,000 products went into your warehouse, your input efficiency—and this is the proper definition of efficiency—is 75 percent. That means 5,000 caps just went somewhere,” Zepf explained.

Many companies dismiss scrap as “part of the process.” One of Zepf’s presentation slides showed product spilling out from overflow tables and overfilling a Gaylord container. That company considered that a good day because it usually filled six Gaylord containers of waste at least every hour. “If they actually counted waste, it would have been about nine percent of the product on that ‘good day,’” he said. “You can’t stay in business by doing that. They were running their line at a pretty good rate, but they dumped too much product.”

He said a simple Excel spreadsheet can help a manufacturer get a handle on the different factors that determine OEE. “When you’re talking about a packaged product, you have to consider not just the product, but the bottle, cap, labels, tamper-evident band, carton, shipping case, pallet, stretch wrap, and any other inputs,” Zepf stated. “Go after your most critical inputs, those with the highest costs. The scrap from those inputs relates to your costs of quality. Most companies don’t even look at scrap, so there’s no value placed on it and it’s not measured in their OEE.” He noted that the highest scrap rate he’d ever seen at one plant was 22% of the product, and that was not in the semi-conductor industry.

Food versus pharmaceutical OEEs

Zepf also compared OEE between food and pharmaceutical facilities. He estimated that the OEE for a World Class pharmaceutical company is about 67%; 85% for a World Class food operation. “I have allowed some differences due to the nature of the businesses, although I don’t buy the, ‘Oh, we’re so regulated’ pharmaceutical reasoning. The food industry faces regulations as well. In fact, I’ve been in some slaughterhouses that have better procedures and more cleanliness than some pharmaceutical plants,” he said. “What I see in most pharmaceuticals is 15-percent to 45-percent OEEs, with 7 percent the lowest I ever measured, compared to a 35-percent to 65-percent OEE range in the food industry.

“The target should be around 85 percent. There’s a reason for the [food/pharmaceutical discrepancy]. I can understand some of their [pharmaceutical] problems, but a lot of them, as it was told by me a few years ago, is related to economics. I was told that some pharmaceutical firms said they knew it would only cost a couple of thousand dollars to fix a problem, and that investment could save $50,000 to $75,000 a year, but the product on that pallet over there is worth 2 million dollars. What incentive do I have to spend a couple thousand to gain $50,000?”

When asked if he saw any improvement in the pharmaceutical sector recently, and what he saw in the future, Zepf said: “There is an improvement that I see in terms of people talking about it more and becoming more active about it, but the problems are that they’re not measuring OEE correctly, nor are they looking at it correctly, so they won’t be as successful as they think they will be in trying to remedy a lot of their problems.”

A PPF audience member asked if Zepf had any recommendations to get management on board to adopt OEE? “That’s a tough nut,” Zepf admitted. “Back in the 50s and 60s you couldn’t fool the president or the CEO because he knew how things worked. Nowadays they only look at numbers, so the only way to get their attention is if you actually do OEE correctly and can provide numbers that have an economic impact. Then they’ll ask, ‘Why haven’t we done this?’ Well, because we haven’t gotten approval yet. ‘Well, here’s the money, get that done’ may be their response.”

Zepf expressed concern that engineers are poor in presenting their case and presenting a justification. “OEE is a tool that you can use to quantify certain things that enable you to present your case and sell it to upper management,” he said.

One final concern Zepf shared with this editor: What happens when the economy rebounds and there’s less incentive to employ OEE?